- Science Simplified

- Posts

- This week in science

This week in science

Welcome to another This Week in Science! Hope you enjoy today’s articles, let me know what you think in the polls at the bottom or by sending me an email.

We’ve all heard of our circadian rhythm, or our body’s natural sleep/wake cycle. It turns out that the circadian rhythm effects much more than just when we get tired. According to this article, roughly 50% of human genes follow a circadian cycle, making timing extremely important.

A new article found that many genes related to drug metabolism follow a circadian rhythm, making drugs more effective at certain times of day. It’s an interesting finding that might play a role in when we take specific types of drugs (vaccines, anti-inflammatories, chemo, etc).

Both articles are solid writeups on the same research paper, the first is more broadly accessible and the second is more technical, but still understandable if you’re looking for more detail.

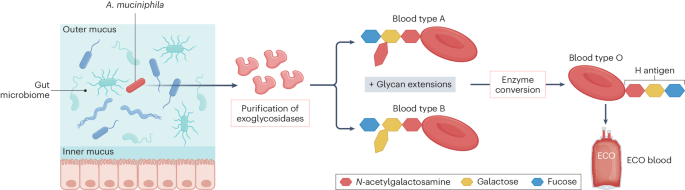

Donor and acceptor blood types need to be compatible in order for a blood transfusion to work, otherwise the acceptors immune system attacks the donated blood cells. The specific molecules on the surface of blood cells determine if the blood is “compatible” or not. The scientists found a specific enzyme that converts other blood types like A and B into type O, which is the universal donor.

This would be a huge step towards creating universally available blood supply and go a long way to addressing the blood donor crises.

Ever wonder how modern displays like QLEDs get their color? It’s through quantum dots, or nanoparticles that give off color depending on their size due to quantum effects. The discovery of these quantum dots won a Nobel Prize earlier this year.

Weight loss drugs like Ozempic are all the rage. They work by mimicking the hormone used by our bodies to tell us we’re full and therefore lead to less eating and subsequent weight loss. Unfortunately, this strategy appears to only work while people are actively taking the drug. After stopping the weight loss drugs, many people regain the weight they lost. However, it seems like a good amount of people only gain back a partial amount of the weight, leaving many lighter than when they started.

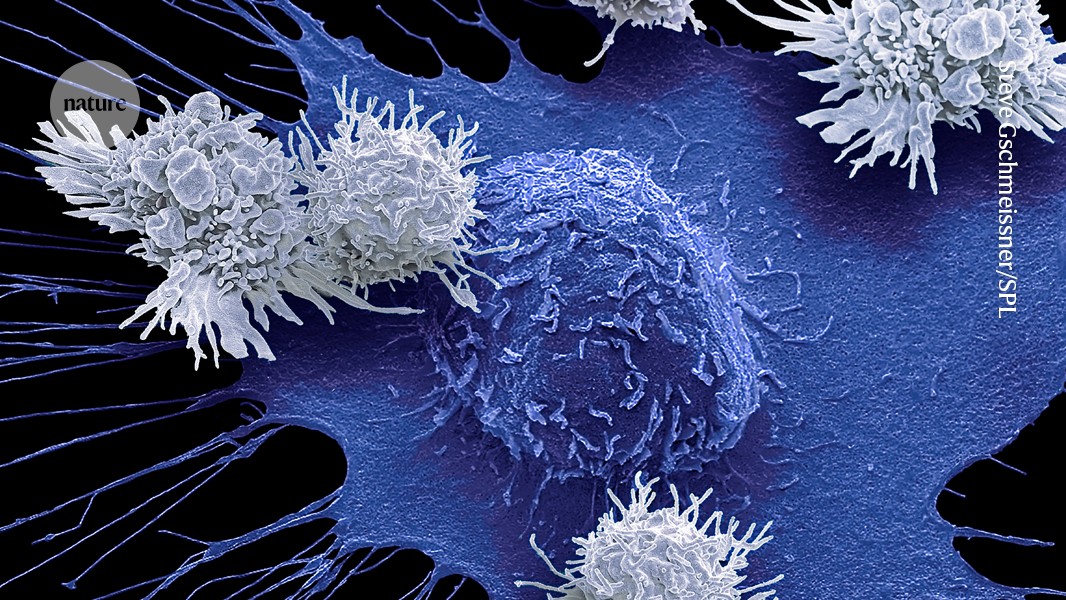

The headline is scarier than the content. CAR-T therapies are one of the newest, and most effective, cancer therapies ever invented. They involve engineering the patients’ T cells to find and kill cancer.

However, the FDA recently launched an investigation to see if the CAR-T therapies cause immune cell cancers known as lymphomas. As of March, they received 33 reports of lymphomas out of ~30,000 people who had received CAR-T therapies, or roughly 0.1% of the patients. Given that these are cancer patients who likely already didn’t respond well to first-line treatments like chemo and radiation, this seems like an acceptably small risk to me.

We’ll see what the investigation turns up, but if it’s this low of a risk then it doesn’t seem all that concerning as of now.

That’s it for this week! Hope you enjoyed this week’s picks

See you next week for more science,

Neil

If you liked this post and want to keep getting cool science delivered to you, sign up for free:

Reply